THE WHEELBARROW MAN

Sample from Kill The Buddha

There’s a place called Caracas where the country is rich and the people are poor. In that city in the valley of the Cordillera de la Costa, where the sun is always close, the people live in a grey and green place, where the concrete and steel inosculate with the trees and the vines, intertwined and inseparable, and the human and the prehuman cohabitate. It’s a place where colorful tropical birds perch atop the rust-streaked corrugated steel roofs and the colonial suburban walled fortresses.

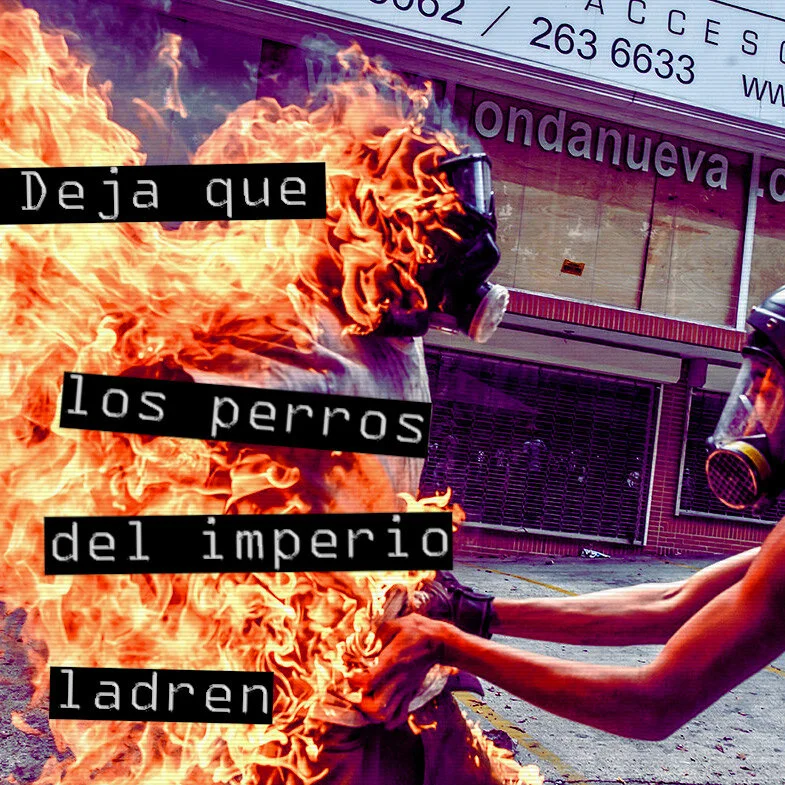

It was just a couple years ago. Some people might tell you about the masked man they saw pushing a wheelbarrow with a dead woman through the streets. Many people wore masks that year but this one was different. Few people took notice. Those that noticed remember him well. It would be a simple mistake to not see it. There was a lot to see that July. The students were marching in the streets and holding signs and starting fires, dressed colorfully, chanting anger, and the police in their armor and with their rifles quarreled with them every day. Streets might have moments of peace but there was always a riot somewhere.

Through the truck tire smoke and over the streets wet from riot control hoses, the wheelbarrow man pushed his quarry through the violence and noise and he bothered no one and no one bothered him. Clothing covered every inch of him. Hands gloved, hood over his hat. Even his eyes were invisible behind his grotesque mask. The girl was limp, her eyes open just the slightest bit like she was just waking from a deep sleep, but she wouldn’t. The head wound just above where the skull and spine meet would make sure she never woke up. Her arms and legs dangled out the side. Her mouth was just barely open. The blood on her was crusted and rust-colored. Flies were just catching their first whiff of her and scouting her for places to feed themselves and lay their eggs in any openings in her, natural or man-made. No one asked him about the girl in the wheelbarrow or about the large canvas bag that sat in her lap.

The wheelbarrow man pushed the girl through narrow alleys of Caracas, past men smoking cigarettes and sitting on milk crates and women tearing feathers out of limp chickens. He walked under highway overpasses where vagrants slept. He crossed wide roads where cars should be driving but the only cars on those roads were on fire. When people saw the wheelbarrow man, they said to themselves that he must be taking her somewhere to bury her. Those that didn’t see that she was dead thought maybe he was taking her to a hospital. People thought of many good reasons not to go inside and call the police or to ask him about his grim errand.

Everywhere the wheelbarrow man walked, he and the girl were watched by smiling Chavez. Road signs, murals on the sides of buildings, posters on walls, statues of him. Everywhere you went, the dead man Chavez was always there, watching with enormous kind eyes and bright white teeth like a saint who could answer your prayers. Godlike in his size and his inescapable presence. He smiled over the shelf-empty stores with eight employees promised jobs. He smiled over the lines of people that wrapped around the block, waiting to offer their fingerprints to bureaucrats to get their ration cards. He smiled over the overcrowded jails and the fallow farms. He smiled because not even death could stop him from inflicting his love on the skinny people of Caracas.

Whenever he found a road where there were demonstrations and counter-demonstrations, and angry people packed the streets, the wheelbarrow man and the dead girl were patient and watched and waited on the sidewalk. This was the second year of riots and now the rioters and the riot police were experts in their vocations. Protesters attacked the police with stones chipped from the corners of buildings and bottles filled with gasoline. The police returned violence with high-pressure water cannons that knocked people prone and broke their skin and tumbled them away like a leaf blower pushes leaves. They fired gas cans to make breathing and seeing impossible and the military marched through the streets and the people who were their enemies retreated at the same speed, hurling objects and insults and accusations. When they the protesters were pushed back to a T in the road, the paramilitary socialist biker gang, The Collectivo, were already there waiting on both sides revving their motorcycles; angry, gas-thirsty machines that growled like two stray dogs fighting over a fish head. There were a lot of them, past counting, sometimes with two of them on one bike. They wore cloth masks with skulls and were armed with pipes, knives taped to broom handles like spears, screwdrivers filed sharp, chains attached to concrete chunks with ring screws, and sometimes guns from military surplus. The rioters fell into a trap, pinned in three ways. The police stopped their march and let the Collectivo do just as the paramilitaries always do.

The cops didn’t do any of the fighting that came next. They let the gang do it for them. There wouldn’t be a punishment for any of them. The Collectivo ran down protesters, beat them, drove over them, shot them, and choked them. Some protesters fled towards the police line and the police beat them for it or fired cas cannisters at them at close range. Some tried to rush past the gangs but the bikers ran them down and crippled or cut or crushed them under their tires. A lucky few escaped through the doors and windows of shops or down the alleys or up the metal fire escapes or just snuck away through all the chaos.

The twin-cylinder cavalry left their mess for the police to clean up after. Police arrested whoever they found on the ground and cuffed them and threw them into busses, even the dead ones. When it was mostly clear, the wheelbarrow man and the girl crossed the street like a nurse waiting for the green light to cross with a wheelchaired patient. The police didn’t bother him as he crossed their path.

The macabre pair began their steep-angled ascent up the mountain road, through the shantytown that covered the side of the mountain. The barrios were homes stacked on top of one another up a cliff-side like a ziggurat designed by drunks, brick and stucco, rusted steel sheeting for roofs, brown drainage pouring between the streets ankle-deep, with patches of bright jungle green blooming out of it where the earth wanted back, electrical and cell towers poking out here and there, and at the highest points the clouds clung to the mountain and hid its true height. A ramshackle town where electrical cables haphazardly zigzagged above and between the homes, held together by duct tape and prayer, attached along gutters, and slipping through glassless windows into homes made of concrete and scrap metal and trash and the generosity of neighbors.

At the lower levels, windows with irons in decorative patterns because if your home is a prison, make it look otherwise. Homes two-toned, white and teal, muddy red and corn yellow, faded business signs that should have been replaced a generation ago. Children wandered in groups with soccer jerseys and no shoes. Spray paint marked every wall with political slogans praising Maduro for all he gave them but just the one colorful mural of Chavez, defaced with a black marker, mustache and missing teeth and insults on his face alongside an unblemished image of El Libertador Simón Bolívar.

People would look up when they heard the creaking of the wheelbarrow and the steps of his boots and when they saw him they always walked away and minded their business. Up the winding and steep road were hardly any cars. At the top, the clouds perched and swallowed the horizon. Down a side road, there was a morgue with dozens of families outside waiting to identify their loved ones for the previous night’s body harvest. Some from the police, but more from the gangs. Women wept and asked God for explanations. Priests insisted He had them but God would neither confirm nor deny the priest’s accounts.

Stray dogs of all colors and patterns gathered in packs and wandered the streets. They made doe eyes at people for scraps, humped and nipped at each other, and made war on other packs from time to time. But the dogs wouldn’t bother the wheelbarrow man. They all moved aside and lowered their heads and tails in respect and let him pass without even a curious sniff. They paused their dog chores and watched the pair walk away and when the man and the woman were gone the dogs continued to be dogs, not peasants supplicating to a strange, grim king touring their village.

The sun was coming down, and the jungle was getting louder and the streets were becoming more empty. The boys in the streets at sundown, the ones whose parents couldn’t control, the ones with knives and bats, saw the wheelbarrow man walking through. When they approached him he looked into them, not at them, and drank their young man’s courage. The boys used strong language and terrifying threats but their eyes wouldn’t be steady and their throats were timid and the words came out as yelps, not barks. The lawless boys moved from his way and didn’t tell anyone what they saw. Half-grown boys, desperate to become men, knew better than to tell others that now they believe in childish fairy stories about monsters.

When he reached the higher points of the shantytown, the wheelbarrow man turned and looked to the west. The blue sky caught purple and orange fire behind the clouds and glowed a warm paradise glow over the city in the valley. The insects and the creatures of the jungle got louder as the sun went down. The wheelbarrow man turned and continued his long walk up the steep road and into the fog. At a high point, where few people built their homes and the place became colder and the air took 2 breaths to breathe instead of just 1, he found a spot of dirt that was empty save for a few bricks stacked in a pile. It was the empty lot of an abandoned construction project. He parked his cart there and removed the canvas bag and set it on the ground. Things were just getting dark, where objects were mostly black and only visible as silhouettes against the hot purple firmament. He delicately removed the girl and placed her on the earth and he sat on his knees and placed his hands together and bowed his head. He began a chant in a language that very few in Caracas knew existed, let alone heard with their own ears. He spoke his chant in a monotone hum that blended with the hum of the countless creatures in the jungle. He prayed over the girl in a roofless temple of nature and the congregants were all the black-eyed things hidden in the hungry wilderness. Their chirps and buzzes and growls and squawks were a chant along with him. When his song was finished, he opened up the canvas bag and removed a 10-inch bladed chainsaw and started it with a tug on the ripcord.

In the barrios below, the people heard the machine sounds coming from the place where the wheelbarrow man had gone. They had no windows to close and hide from the noise and no courage to go up and stop them. Mothers telling their children bedtime stories told the stories louder. Police turned up the sound of their scanners. Young men with pockets full of zip guns and knives turned up the music on stereos on the stoops where they sat. Men turned up the radio to hear the play-by-play of the match between Aragua and Deportivo Anzoátegui.

The next day, no one went up the mountain. When people asked each other, none had seen the wheelbarrow man come back down. It was three days before a young policeman volunteered, encouraged by the words of young, pretty girls. He went up there with his gun and when he came to the foggy spot of earth, he found no wheelbarrow and no man. The girl was gone too, but only by half. Most of the meat of her had vanished, picked apart by de-domesticated dogs and wild sharp-toothed animals and pick-beaked birds. Pieces of her lay in neatly stacked, mostly the yellowish-white of bone and a hypnotic swirling of black over it of the ants and the flies. The tiny little black things climbed into where her eyes used to be and through the nose and between her teeth.

That was two years ago. The people on that street still sometimes mention the wheelbarrow man but never above a whisper. Children are forbidden to walk up to that desecrated pagan shrine where a stranger fed a girl to an ancient god of stone and fog. El Hombre Carettilla never came down from that place. Some say he became immortal by the sacrifice, but cursed to never leave the mountain. Some say the girl was his love. Others say the girl was his victim. A few say both. The less superstitious people say he was a mad killer like El comegente Dorángel Vargas. Some say he was a gangster sending a message.

Whatever the truth is, the barrio knew two gods flanked them. The one in the valley with a smiling face as large as a building and a thing in the mountain jungles without any face at all.

It’s a fun little urban legend but you’re not here for the fairytale of the wheelbarrow man. I only told you that story so I could tell you this next story. But it’s not my story to tell. The guy it did happen to? He’s not here to tell it so you got me instead. Pay attention to the details and try not to judge anyone too quickly. This is a true story about things that didn’t happen.